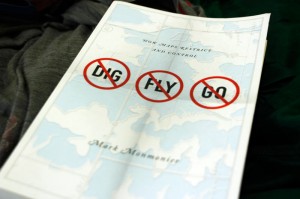

No Dig, No Fly, No Go

I bought this book while in New York (ever so briefly) to read on the plane flight to Ghana; I saw it at a large chain store on the “notable non-fiction” table whilst purchasing a book to send to my mother. Jay (my global health mentor slash professor) had previously told me how UW’s “most radical department” is probably the geography dept, and for that reason when I saw a book that combined geography and what seemed to be structural violence, I figured it was worth the price.

I bought this book while in New York (ever so briefly) to read on the plane flight to Ghana; I saw it at a large chain store on the “notable non-fiction” table whilst purchasing a book to send to my mother. Jay (my global health mentor slash professor) had previously told me how UW’s “most radical department” is probably the geography dept, and for that reason when I saw a book that combined geography and what seemed to be structural violence, I figured it was worth the price.

The back of the book promises:

Some maps help us find our way; others restrict where we go and what we do. These maps control behavior, regulating activities from flying to fishing, prohibiting students from one part of town from being schooled on the other, and banishing certain individuals and industries to the periphery. This restrictive cartography has boomed in recent decades as governments seek regulate activities as diverse as hiking, building a residence, opening a store, locating a chemical plant, or painting your house anything but regulation colors. It is this aspect of mapping—its power to prohibit—that celebrated geographer Mark Monmonier tackles in No Dig, No Fly, No Go.

What I found upon reading that this book wasn’t the abundance of “puckish humor” I’d expected (based on the review by Progress in Human Geography on the back) but simply an academic guide to maps, zoning, boundaries, and their functions in society. At times the book is a bit dry, although I suppose that might be a natural hazard of geography.

“Many political borders serve as semipermeable membranes, often quite open to diseases and yet closed to the free movement of cures.” That is the sort of quote I was hoping to find in a book about restrictive cartography. That, however, is a quote from Dr. Paul Farmer’s Infections and Inequalities, and you will find no overt judgments such as above in No Dig, No Fly, No Go, only straight forward* explanations of how cartography works and how it got to be the way it is. There were also a few points where I wished he would have delved deeper into some issue he was exploring, and instead I found the chapter coming to a close, and the book moving on to an entirely new topic (one good example is microstates — he covers both the legal distance a country’s border extends beyond its shore, and mentions one or two microstates, but fails to touch at all on the Principality of Sealand).

So in a way I was disappointed; this was not the 200 page essay on structural violence I’d hoped it would be. But in a way I was pleasantly surprised; it was quite readable and I feel now much better informed as to zoning laws, how borders are agreed upon (or not), and why certain Antarctic research stations are located where they are. While this isn’t the sociological trove I thought it might be, it probably is a must read for anyone who plans to build a home (or buy property) without significant legal advice.

*Assuming you aren’t rattled by sections like: “Beginning at a stake standing at the Northwest corner of the property to be conveyed at a point on the East line of the Highway leading from Redfield to Minor’s Landing adjoining land of Clifford Hopson and running thence S 883/4 degrees East, 20.4 chains along land of said Clifford Hopson to land of David Raup as the fence now stands…” (In fairness this is not Monmonier’s text but that of a survey he examines)