A year has gone

It’s been just over a year since I returned from Africa, and it feels like the time to collect my thoughts has come. Many people I know have since asked me to tell them about my trip, or asked me how my trip went. I have struggled, and still struggle, to find a way to succinctly summarize my experiences. The best I can do is to say that the time I spent in Ghana and in Nigeria was, without a doubt, life changing. I left a piece of my heart in Africa, and in its place I brought back a new perspective on the world, on humanity, and on how we relate to each other.

If this is your first visit to my blog, you’re welcome to read this post, but it might make more sense to start at the beginning (bottom of this page), with the “We’re in Ghana!” post and work your way forward chronologically. At the very bottom of each post is a set of two black boxes with white arrows; if you click the left-facing one it will take you to the ‘next post’, and eventually you’ll arrive here.

Before we left for Ghana I spent a good deal of time researching, reading about Ghana, interviewing others who had spent time living there, in hopes of avoiding major pitfalls and social faux pas. One anthropologist I interviewed gave me a lot of good insight, despite the fact that her own two-year experience living (and working as an anthropologist) in Ghana had effectively ended her desire to remain in her chosen field. She returned to the United States from Ghana with a masters in anthropology, and when I met her she was working as a waitress. Reviewing my notes from the two-hour interview I conducted with her in March of 2010, the first thing she said was “their first question will be, ‘what did you bring us?'” It was this expectation that Westerners are there to ‘save’ them, to give them things, that was off-putting to her. She told me of a school project in her village:

A farmer had donated some of his land so that a school could be built by UNICEF. Something went wrong during the construction of the school, possibly with local contractors, and UNICEF pulled out of the project with it halfway finished. The villagers could have banded together to finish the school, but their expectation was that some other NGO would come in and do it. No other NGOs were interested, because then they would have to share credit for the school with UNICEF. So the half finished school sat, perennially half finished, covering previously useful farm land.

In a way, her experiences helped to immunize us against some of the damage and perceptions created by Western tourists, aid workers, and “voluntourists”. Where she had gone to Ghana as perhaps a slightly-too-naive masters student, we went as amateur ethnographers who were aware of this and other unfortunate phenomena. Much has been written about the aid culture, perhaps most notably by William Easterly, Linda Polman, and Robert Chambers. What is most sad is that in a paradigm where Africans are supposed to benefit from the benevolence of others, it is the Africans who are most victimized, while the ‘benevolent’ generally get to feel good about the charity in which they have engaged, never knowing that schools are left half-built (amongst other injustices), and those they “helped” might actually be worse off for the “help” they received.

I am a person of privilege. By virtue of the nation of my birth, I am rich. By virtue of the color of my skin, certain benefits nearly the world over are conferred to me. By virtue of the education I have been fortunate enough to receive, I am in a position to make a difference for others. It seems to me that the moral question of the remainder of my life has a clear answer. If my goal is to serve others, I can think of none more deserving than the poor, than those with the least access to education, to healthcare, to the basic fruits of science and technology. Whether my service will ultimately be to those in my own country, or to those in Ghana, Nigeria, or elsewhere, it is more clear to me today than ever that nothing is more important to me than working to undo these structural injustices.

It can be difficult, at times, for any of us to have the necessary empathy for others. As someone for whom empathy comes easily, I find myself forgetting that empathy may sometimes be absent for some. In Nigeria, traveling with a [Nigerian] nurse-midwife, seeing children who were dying of malnutrition, we were all outraged. The direction of our outrage differed, however. The nurse found herself upset with the parents — upset that they had forgone vaccination of their children (which was free at the local clinic), upset that they had sometimes failed to seek treatment when their children fell ill, upset that some of them simply left their child’s survival “in the hands of god.” This was upsetting to me too, but I did not, and do not, direct the bulk of my outrage to these parents. The parents are nearly as much the victims of structural injustice as their children.

For me, I think, it was easier to see that parents may not understand the benefits of vaccination. That they may not trust the health workers who offer vaccinations. And that in an area where one in five children will die before its first birthday, and where the average family will have more than five children (and thus experience, almost inevitably, child death), it is easy for me to see how parents may become fatigued — that parents may come to feel as though anything they do is nearly ineffectual, that life or death is solely the will of god.

It was, I think, easier for me to see this, than for our Nigerian nurse. I had presumed the nurse would have an even more lenient viewpoint than I, and I was surprised to find that was not the case. She, being a Nigerian, is much closer to the situation than I, and more likely to impose her own worldview on those we encountered. I understood going into this that there was almost no way any Nigerian villager would share my worldview, and this allowed me to be more open to seeing their own. What it taught me is that I must work to have more patience, more empathy, for those in the United States. In the months since, I have found myself, on occasion, about to pass silent judgment on someone in my own country, and found the need to pause and remember that the closer one is to a situation the harder it may be to find empathy for those who are victims of that situation.

I spent much time driving to remote areas with this nurse, discussing the nature of humanity, and my viewpoint at the time was that most, in fact virtually all humans, will act in a way they feel to be rational. For instance, [virtually] no parent wants to harm her child. So the question is, if harm does come to a child, what went wrong? If we can accept the premise that humans generally act in a way they feel to be rational, then why did the situation that led to harm feel rational to that parent? Why, for instance, might not vaccinating your child feel rational? Or why might not seeking treatment for your sick child feel rational? The more I want to condemn someone for failure, the more I must work to first ask myself this question and to be open to empathy.

Another thing we found was, as you might expect, very different attitudes toward healthcare in Africa than in the United States. In Ghana, we encountered a much more collectivist viewpoint than exists in the United States. I cannot imagine mass immunization days taking place in the US, and even if they did, what I certainly cannot imagine is doctors grabbing lone children off the street and immunizing them without parental involvement — yet this is commonplace in Ghana. In this regard, I found Ghanaians to have much more trust of their government and of the public health system than [the typically individualistic] Americans.

Some of the drawbacks of emergency care seemed on par with America. The cost could run into days’ worth of wages, and much of this must be paid up front. Many people circumnavigate the doctor’s office or hospital by simply visiting a local chemist (pharmacist). This is a situation about which I have experienced much ambivalence. The chemists are quick to push antimalarials and deworming medications, two classes of drugs that are no-doubt widely needed in Ghana. At the same time, I found some chemists to have little medical knowledge at all (or even English fluency), and they are undoubtedly pushing drugs which may be inappropriate for many patients. Anyone with a fever or headache will get malaria treatment. For many this will probably be the correct course — for some it will not. A doctor would be more able to make that diagnosis, but many of those who visit a chemist are unable to afford a doctor.

In Nigeria we found many, many measles patients who had first seen a chemist for treatment and ended up with either Tylenol or antimalarials (before finally going to the hospital when those did not alleviate the problem). So I don’t know what the answer to the chemists is; they do harm, but they also do much good for a large segment of the population that otherwise would have no access to medical care. My ultimate answer, is of course, to make the fruits of public and social health available to all as a human right, but this will not come soon or easily.

In general, in Ghana, large stores do not exist. In fact, there are really very few ‘walk in’ types of stores. If a store has a roof, it’s generally either a container shop (made from a corrugated steel shipping container), or maybe a small concrete shop or a plywood ‘booth’. Much of the commerce in the country takes place on street corners and out of small booths. In the capital city, Accra, there is a mall, frequented by whites and by affluent Ghanaians, and in the mall there are a couple of dozen Western-style shops. The Accra Mall reminds me of a low- or mid-level mall you might find in a random medium-to-large sized American city. With the exception of the mall, though, there is really no sort of organized aisle-based Western-style commerce.

One of the first things to strike me is how alien most Ghanaians would find the United States. How simply overwhelmed I was when entering a grocery store again for the first time. Rows and rows and rows of well stocked, nicely lit, neatly organized products. I do not think, even with an hour of time, could I explain to the average Ghanaian what a Costco or Wal-Mart Supercenter looks like. I mean, I am sure they could grasp the idea of a giant building full of products, but really I don’t think they could understand it. It was these unnoticed differences that stuck me most, I think, when returning. You can buy apples here, and you can buy apples in Ghana, but the experience is very different. For all of the potential pitfalls in Ghana’s way of doing things (lack of health codes, or at least enforcement thereof, etc), I have a lot of preference for Ghana’s way — 99% of the time when we bought something, we were supporting an individual person or family from our neighborhood, rather than a faceless multinational corporation.

I also think our difference levels of infrastructure and have benefits and drawbacks. Americans feel very entitled. If your electricity shuts off, you’re likely to call the electric company right away. If your Internet stops working for a few days, same deal. If you turn on the faucet and no water comes out, again, someone is going to hear about it. In Ghana, these are simply things people accept as a way of life. On one hand this is unfortunate, as it felt to me that it breeds a certain amount of permissiveness when it comes to infrastructure failing — how much urgency is there to get the water working again if no one is going to call and complain. If you’re a high-level manager at the water company and some client walks in and wants to pay you $1,000 to divert half of the city’s water to his project for the day, well, you’d be tempted to take that money, knowing you could probably get away with it.

On the other hand, our obsessive expectations about things working, always and instantly, must create a certain amount of stress in our lives. Comedian Louis CK tells a joke about a friend complaining that airplane seats don’t recline far enough, and Louis has to angrily remind him that he’s in a magical metal tube flying through the sky at hundreds of miles per hour — the message is that he should just shut up and be happy for what he has. In the same way, I think Ghanaians are very good at this. They take the good with the bad. They shrug when the water or electricity doesn’t work, and move on with their lives. Americans are more likely, I think, to bottle this sort of thing up, or take it out on others. Either way, we must carry a certain amount of allostatic load that Ghanaians simply do not. So the next time your cellphone can’t get reception for you to load a YouTube video, just remember: it’ll work again soon. I found that Ghanaians had developed admirable social modalities for dealing with the various stresses and unpredictable elements of daily life; most Americans could learn a thing or three from the average Ghanaian.

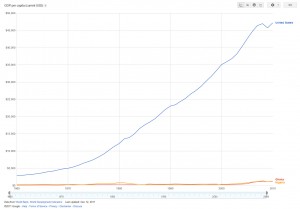

Maybe the most significant thing I learned from my experiences in Ghana and Nigeria, was that inequality didn’t present exactly the way I thought it would. In global health we use indicators much of the time. Indicators are great little tools, they are things you can measure, and through inference they can tell you much about a society. But it’s important to know what indicators to measure. Indicators like infant mortality, per capita income, and so forth, are common and time-tested. The age at which the average person will die (life expectancy) is another very commonly used indicator. Countries with robust public health tend to have very good stats — places like Sweden, Iceland, Canada, Japan, all have very good infant mortality, life expectancy, and so on. To some extent income is a factor here, but only to a certain level: once your country is “rich”, the overall public health strategy will matter a lot more than whether an average person makes $25,000 or $45,000. This is evidenced by the fact that the United States has one of the highest incomes in the world, but ranks very poorly when compared against other OECD nations that have lower income levels (but better overall public health measures).

Maybe the most significant thing I learned from my experiences in Ghana and Nigeria, was that inequality didn’t present exactly the way I thought it would. In global health we use indicators much of the time. Indicators are great little tools, they are things you can measure, and through inference they can tell you much about a society. But it’s important to know what indicators to measure. Indicators like infant mortality, per capita income, and so forth, are common and time-tested. The age at which the average person will die (life expectancy) is another very commonly used indicator. Countries with robust public health tend to have very good stats — places like Sweden, Iceland, Canada, Japan, all have very good infant mortality, life expectancy, and so on. To some extent income is a factor here, but only to a certain level: once your country is “rich”, the overall public health strategy will matter a lot more than whether an average person makes $25,000 or $45,000. This is evidenced by the fact that the United States has one of the highest incomes in the world, but ranks very poorly when compared against other OECD nations that have lower income levels (but better overall public health measures).

Ghana and Nigeria are interesting examples because they are similar when we look at certain indicators. I had studied a lot about Ghana before leaving on our trip, but didn’t know much specifically about Nigeria (beyond my general background knowledge). Partly this was because we knew at the beginning of the trip that we would be going somewhere with a measles outbreak, but not where, exactly, that would be. It might have been Zambia (which was at the tail end of a huge outbreak at the time), Nigeria, or a couple of other places. Within Ghana I spent some time looking at Nigeria’s indicators once we knew that’s where we’d be going, and indeed they did look similar to me. (See image above.)

Before all of this, I’d studied global health both informally and in a college classroom environment, having taken two 400-level global health courses that were heavily indicator-based. I considered myself pretty sharp when it came to indicators. If you’d told me how much money the average person in a country earns, I’d have guessed I’d have a good shot at divining the top three causes of death, proportion of population under 15, and so on. What I hadn’t really realized is how much ‘averaging’ can skew the real picture on the ground.

Before all of this, I’d studied global health both informally and in a college classroom environment, having taken two 400-level global health courses that were heavily indicator-based. I considered myself pretty sharp when it came to indicators. If you’d told me how much money the average person in a country earns, I’d have guessed I’d have a good shot at divining the top three causes of death, proportion of population under 15, and so on. What I hadn’t really realized is how much ‘averaging’ can skew the real picture on the ground.

A year later when I think back to what I learned in West Africa, to what will never leave me, the most striking thing I learned is that any statement made about a population cannot be viewed without context to the stratification within that population. I feel now pretty strongly that poverty is not as important as relative poverty. Allow me to try to explain what I mean by this. When viewed on paper, Ghana and Nigeria have about the same levels of income per average person — that is, the average person on the street that you’d pass probably earns about $1800, maybe $2000 per year (according to the World Bank).

When we arrived in Nigeria, I was surprised to see that it was significantly more developed than Ghana. Lots of little clues almost right away led me to realize there were way more persons of wealth and privilege there. The freeway overpasses and general construction looked way more ‘solid’ than in Ghana. I saw more expensive cars in traffic (and more cars in general). What didn’t immediately occur to me, but soon would, was that for every person who makes, say, $20k per year, in order for Nigeria to keep its $2k average income that means nineteen or so people have to make around $1000 instead of the “$2000” that the ‘average’ income would suggest. Or to say it another way, the income averages out to $2k per person, but the spread from poor to rich is greater in Nigeria than in Ghana. It is this stratification that is really critical.

The first night we were in Nigeria we stayed in Abuja, the capital city. Our contact at UNICEF, who was one of the nicest and most helpful people I’ve ever met, got us a bargain-basement UN price at a local hotel. Our room, comparable to something in the U.S. that you might find at a Motel 8, was $200 per night. With discount it dropped to about $100. WOW. Needless to say, after months of trying to live on $8-10 per day (for food and lodging), this was a shock. We’d actually only come into the country with about $500 in cash.

After we moved on from Abuja to Kaduna, the UNICEF office there again had more supremely helpful employees, one of whom drove us in his own car to the cheapest hostel any of them could think of. It was a Catholic guesthouse, and our room was $40 per night. We had electricity and water for a handful of hours each day. This room was comparable to the guesthouses we’d stayed at in Ghana, except those had typically been $8-10.

So where am I going with all of this hotel rambling? Right away in Nigeria I noticed the prices of things seemed to be at least three times whatever they were in Ghana. Sachet of water? Three times. Guesthouse room? Four times. Now, many of the things that we purchased were marketed towards those with money, so the price inflation for staples (rice, casava, etc) might be less marked, but my overall point is this: as your society has more and more wealthy folks, those folks are prepared and able to pay more for goods and services. Prices go up. Those who are not wealthy are less able to afford goods and services.

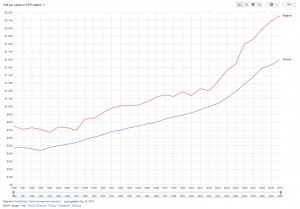

The link I give above goes to per capita income expressed in PPP dollars — purchasing power parity. This indicator is supposed to take into account things like the cost of bread, clean water, and so on, to get at the real income of the average person. If you are living on a dollar per day, it really doesn’t matter if your neighbor drives a Mercedes or not, a dollar isn’t going to cut it. But, if you are living on $6 per day, whether a bag of rice is $3 or $9 is going to make a big difference in whether you can eat or not. And whether your neighbors with the luxury cars and disposable incomes are buying rice might inflate the price from $3 to $9. Absolute poverty is important, but so too is relative poverty. To give another example, $12 per hour might be an okay wage in Iowa; in San Francisco it will be much more difficult to live on such a wage. The wider the stratification of income within a society, the greater the problems for those on the wrong side of the fault lines. Ironically, the PPP chart actually shows Nigeria as having more purchasing power — this was not my experience.

The link I give above goes to per capita income expressed in PPP dollars — purchasing power parity. This indicator is supposed to take into account things like the cost of bread, clean water, and so on, to get at the real income of the average person. If you are living on a dollar per day, it really doesn’t matter if your neighbor drives a Mercedes or not, a dollar isn’t going to cut it. But, if you are living on $6 per day, whether a bag of rice is $3 or $9 is going to make a big difference in whether you can eat or not. And whether your neighbors with the luxury cars and disposable incomes are buying rice might inflate the price from $3 to $9. Absolute poverty is important, but so too is relative poverty. To give another example, $12 per hour might be an okay wage in Iowa; in San Francisco it will be much more difficult to live on such a wage. The wider the stratification of income within a society, the greater the problems for those on the wrong side of the fault lines. Ironically, the PPP chart actually shows Nigeria as having more purchasing power — this was not my experience.

Purchasing power wasn’t a concept that was really foreign to me before Nigeria, or even Ghana. What it took was seeing the concept in application in Nigeria to make me realize the power and tragedy of averaging. That is really what I learned in Nigeria. Here was a country with more development than Ghana, yet also more suffering. My initial impressions had been how developed they were compared to Ghana, but once I got to the north, especially to rural villages, I saw many things I would never have seen in Ghana. I saw children malnourished and blinded from measles complications — something that essentially doesn’t happen anymore in Ghana.

I had known coming to Nigeria that infant mortality in the north of the country could approach 200. In Ghana the average is around 50 (compared to Nigeria’s average of 80). To me, fifty infants out of 1000 dying before their first birthday is unacceptable. Eighty is even less so, and 200 is a tragedy of nearly inconceivable proportions. What I learned, almost right away, is that averaging hide these outer bounds, these more marginalized populations. For every Nigerian whose child is delivered in a hospital and has a lowered risk, there is another Nigerian, probably a teen, delivering her baby alone or without trained assistance, scared and unsure of what to do, at great risk for infant death, maternal death, fistula, and so on.

I came back to the US and with my revelation: inequality is what matters! We need an indicator for this! Income, life expectancy, infant mortality, none of these are truly useful unless we can use some other indicator to get at their spread, at the levels of inequality. What I quickly found out was that for income this indicator already exists. The most commonly used indicator for income inequality is the Gini Index. The higher the Gini score, the more inequality.

And when I thought about it, this sort of made sense. Poverty is a problem, I am not denying that. But might inequality be a bigger problem? Might we often be meaning “inequality” when we talk about the ills of “poverty”? Cuba is poor, yet the people of Cuba do not die as if they are poor. They live longer than their counterparts in the United States, they have better infant mortality, and they spend around $200 per year (per person) on medical care, compared to over $7,000 for us in the United States. Cuba has very low income inequality; most people are marginally poor, and there are essentially no extremely poor or extremely wealthy. What I began to realize that is from a public health perspective, once you are not starving to death, once you have your so-called ‘plate of basic needs’, income inequality is a much bigger factor.

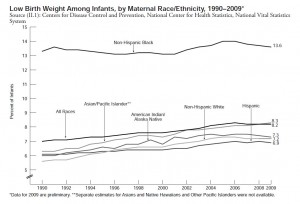

The United States doesn’t have very good infant mortality for a rich nation, but I started to wonder, what effect might averaging have on this. I mean, the U.S. isn’t good to begin with, when we look at the average, but what about when we look at the outliers … how can we tease out communities that are at exceptional risk and see how they deviate from the overall population? If our average is around 7/1000, what is the real number for those who are part of marginalized groups? For African Americans, for instance, infant mortality is about double the national average. What might life expectancy be for the “average” white American compared to, say, someone living on the reservation in Pine Ridge South Dakota?

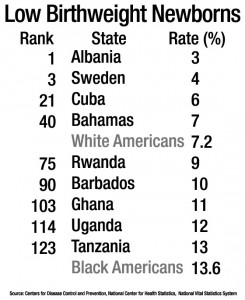

For a little experiment, let’s look at low birthweight newborns. This is a good indicator because I suspect most everyone reading this will be familiar with how dangerous  it is to be a low birthweight baby — this is part of the reason that smoking during pregnancy is so harmful, because it’s closely associated with lowered birthweight. Low birthweight officially means 5.5lbs or less. The U.S. overall average is 8.3% of newborns, which is the highest it’s been in 40 years. This is not a great number, but hidden in that average is an even worse number. What about when we stratify this information by race? Blacks have double the prevalence of whites! In fact, our African American low birthweight stats are so bad that if we use that number alone and compare it to other countries, blacks in America have a higher proportion of low birthweight newborns than many low income African countries: Rwanda, Ghana, Uganda, Tanzania, and so on. (See Prof. Vernellia Randall’s presentation at 6:46.) This is what averaging hides.

it is to be a low birthweight baby — this is part of the reason that smoking during pregnancy is so harmful, because it’s closely associated with lowered birthweight. Low birthweight officially means 5.5lbs or less. The U.S. overall average is 8.3% of newborns, which is the highest it’s been in 40 years. This is not a great number, but hidden in that average is an even worse number. What about when we stratify this information by race? Blacks have double the prevalence of whites! In fact, our African American low birthweight stats are so bad that if we use that number alone and compare it to other countries, blacks in America have a higher proportion of low birthweight newborns than many low income African countries: Rwanda, Ghana, Uganda, Tanzania, and so on. (See Prof. Vernellia Randall’s presentation at 6:46.) This is what averaging hides.

So many American health professionals volunteer to abroad to try to help impoverished countries increase their health outcomes, but what we find if we tease apart some of the statistics is that black health in the United States might actually be worse than in many African countries, when looking at certain indicators. Perhaps those professionals should stay and volunteer domestically, if they feel that those who are at the most risk deserve the most help? Obviously the answer is complicated and multifactorial; I don’t mean to oversimplify, but simply to show that the answer is not cut-and-dried: the health status of some communities in rich countries might be worse than the average status in some poor countries. This realization reframed how I thought about health in America. I knew that we had marginalized sub-populations, but I hadn’t fully considered the extent of their marginalization.

So many American health professionals volunteer to abroad to try to help impoverished countries increase their health outcomes, but what we find if we tease apart some of the statistics is that black health in the United States might actually be worse than in many African countries, when looking at certain indicators. Perhaps those professionals should stay and volunteer domestically, if they feel that those who are at the most risk deserve the most help? Obviously the answer is complicated and multifactorial; I don’t mean to oversimplify, but simply to show that the answer is not cut-and-dried: the health status of some communities in rich countries might be worse than the average status in some poor countries. This realization reframed how I thought about health in America. I knew that we had marginalized sub-populations, but I hadn’t fully considered the extent of their marginalization.

In the early part of 2011 I attended an academic forum on population health, and had a chance to pose my questions to a senior lecturer from the School of Public Health at UW. We talked about infant mortality disparities for black Americans versus white Americans, and I asked how we can tease this sort of thing apart and really get a broad view of the health statuses and disparities within the United States, since averaging hides so much of this.

He explained that it was difficult, and as we talked some more about this concept he invited me to audit his Population Health graduate class. In the Spring of 2011 I did just that. It was a very informative experience — he and another physician named Paul Farmer have both had a significant influence on my ways of thinking, and I wrestle daily to continue to assimilate all of the information and ideas they’ve both put out there. I have been incredibly fortunate to be able to not only attend this class, but to pose many questions in the hopes of wrapping my head around the very abstruse problem that is the determinants of health. In the last year I’ve read countless books on inequality, and still have many dozens left to go. My understanding of the human condition is by no means near complete, but I feel a much more educated and extrospective person now than I did 18 months ago, and I have West Africa to thank.

I don’t yet have the answer on how we can reliably get a broad view of marginalized communities within a population. It is difficult, to say the least. One promising approach is to use economic inequality (the Gini Index) as a predictor of poor outcomes. There are several physicians and epidemiologists who have done pioneering work in this realm, and it’s really quite fascinating. Richard Wilkinson wrote a fabulous book on this topic, and recently gave a short TED talk that does a great job of summarizing his findings, everyone really should watch it.

I was already interested in the social and structural determinants of health before I got involved in this measles project. Going to Ghana, and then Nigeria, I already kne w this was my primary interest — why for instance a child might get measles in Nigeria, but not in the US. It took traveling to Nigeria for me to realize that it’s not just the health disparities between populations that matter, but the health disparities within populations. These disparities amount to life and death in a very real way for literally a billion or more people.

w this was my primary interest — why for instance a child might get measles in Nigeria, but not in the US. It took traveling to Nigeria for me to realize that it’s not just the health disparities between populations that matter, but the health disparities within populations. These disparities amount to life and death in a very real way for literally a billion or more people.

I learned that you cannot generalize about countries, populations, even communities. Within any group there will be those who do well, and those who do poorly. Just because two African nations have the same average income does not mean those nations are the same, or that one public health approach will work well within the other. Our goal should be to alleviate both disease and its causes, whether in the United States or in Nigeria, and to innovate effective and culturally sensitive ways of doing so.

When we started this project, we decided to name our non-profit Change For a Billion in the hopes of being advocates for structural change for the world’s poorest, if even just making available a twenty-six cent vaccine. Before my experiences in Africa I could quote various authors and knew a lot of statistics and figures, but now I have some tiny idea of the significance of those figures — how vitally important it is that we all work together to eradicate the structural harm that immiserates so many innocent people.